Lecture # 2: A Conversation about Loyalty

Value Loyalty Above All Else

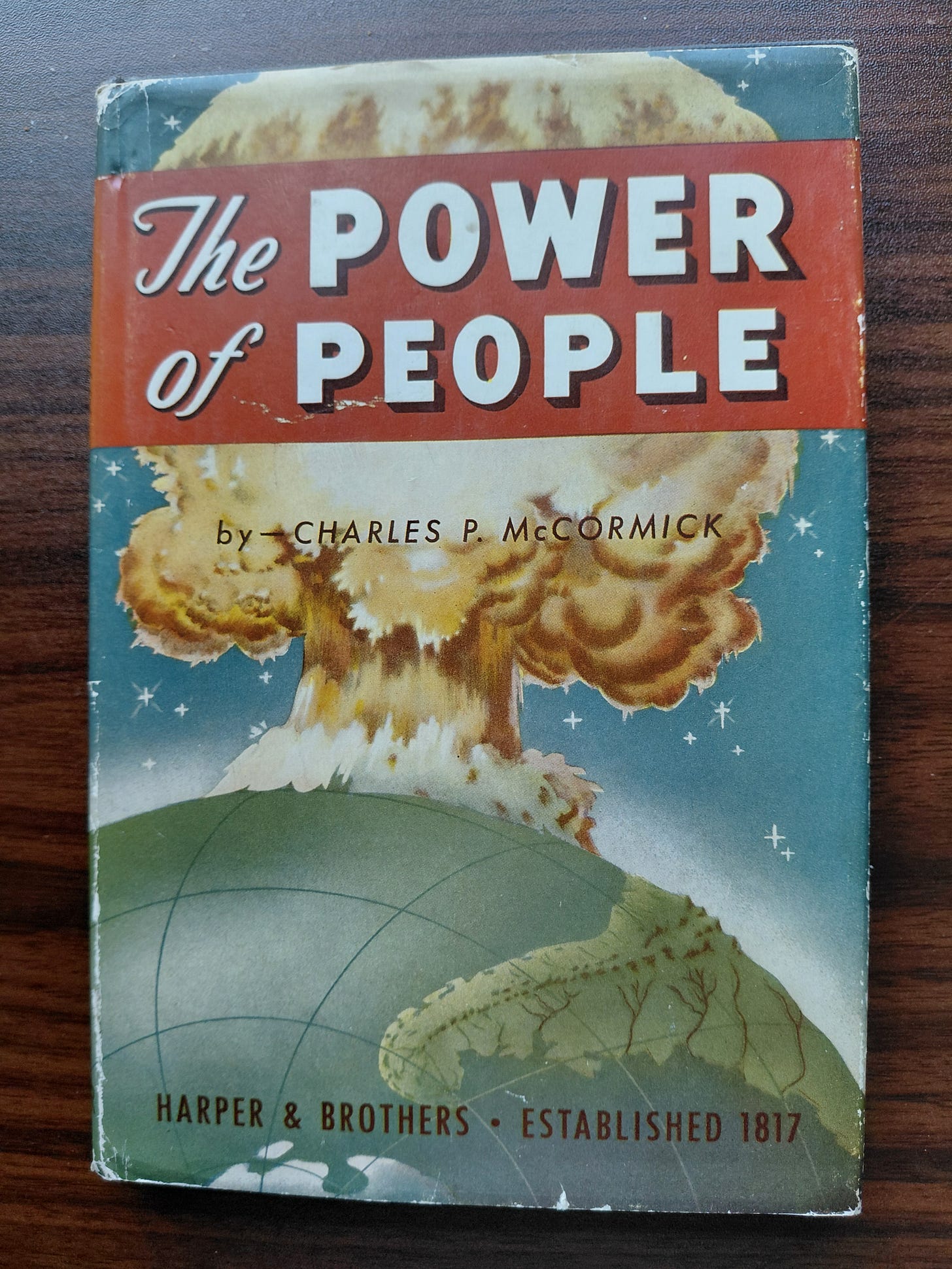

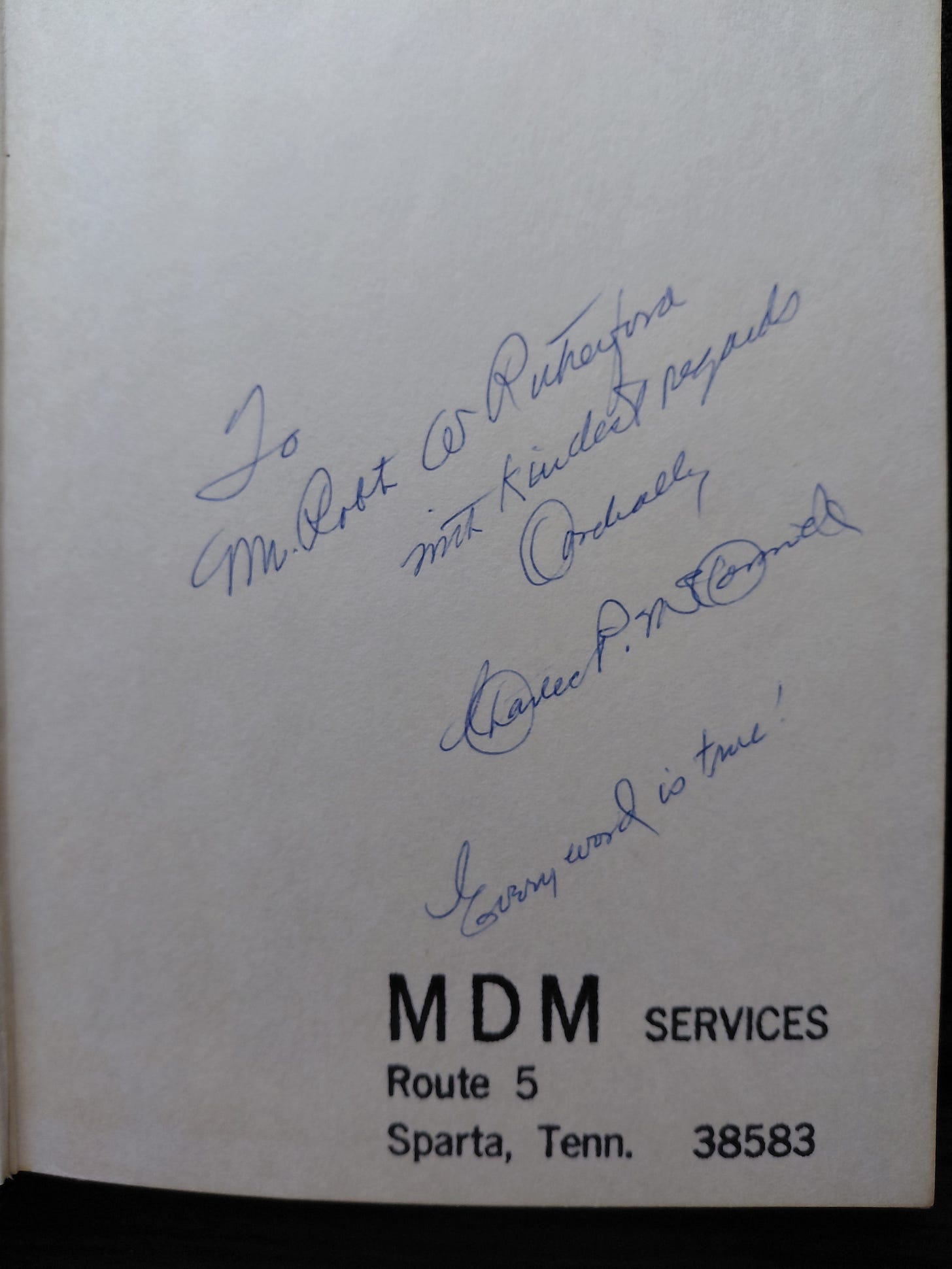

I am convinced that the so-called fictional Raymond Reddington—“The Concierge of Crime,” the elusive figure at the heart of The Blacklist—would have read and admired Charles P. McCormick’s The Power of People. In fact, I can almost see him now, a glass of Bordeaux in one hand, thumbing through page 26 with the other, amused at how a corporate executive could articulate what most syndicates, governments, and conglomerates consistently fail to grasp: loyalty is not purchased—it is cultivated.

This book is priceless and will only be sold to the McCormick &Company organization. It has a one of a kind inscription and story behind it.

One of Reddington’s most quoted lines from the series is, “Value loyalty above all else.” Unlike most CEOs or politicians who invoke the word with the sincerity of a marketing jingle, Reddington understood loyalty as a two-way street. He knew, instinctively, that the counterfeit version—demanded by title, paycheck, or threat—is brittle. In his world, disloyalty had swift, severe consequences.

But in McCormick’s world of factories, boardrooms, and laborers, the remedy was subtler, almost tender: treat people with enough sincerity, justice, and generosity, and their loyalty becomes unshakable.

McCormick writes:

“Loyalty is too precious a thing to be bought and paid for; it must be earned with service that is sincere and just and generous. Therefore, the primary and everlasting purpose of management should be to build every division of its business in ways that will be deserving and worthy of the loyalty of all the people it employs.”

If you close your eyes, you can imagine a meeting between Reddington and McCormick. Reddington, sharp-suited, leaning forward with a mischievous smile: “Charles, my dear man, you discovered what every decent spymaster, mob boss, and apparently even a spice merchant knows—people will betray for money, but they will die for loyalty. You give a man a paycheck, he’ll work the line. You give him dignity, and he’ll stand the line.”

McCormick, with his measured pragmatism, might respond: “Exactly, Raymond. But in business, unlike your world, the loyalty I seek is not born of fear but of pride—pride in belonging, in contributing, in being seen.”

To which Reddington, surely, would tip his hat: “Ah, yes. Pride without the bloodshed. How refreshingly civilized.”

For a young adult reader exploring Dr. Deming’s philosophy, the overlap here is unmistakable. Deming taught that people are not cogs to be managed but human beings whose pride, joy, and sense of contribution are the very engines of quality and progress. McCormick put it to practice in his factories. And Reddington—though his domain was more clandestine—embodied the truth with ruthless clarity: loyalty cannot be coerced; it must be earned.

That is the real power of people.